|

| This is a skull of Peltephilus, a fossorial xenarthran belonging to the family Dasypodidae, which includes modern armadillos. Peltephilus and Ceratogaulas are the only known fossorial mammals with horns! Sadly, no horned fossorial mammals are known to exist today. *Sad trombone* |

|

| Ceratagaulus: The only known rodent to have horns! Here you can see the two horns projecting out of the skull. |

The first piece of evidence comes from the now extinct family of rodents called the Mylagaulidae. Most known mylagaulids had skeletal adaptations for digging through soil, including broad, shovel-like hands with claws to match, and robust limb bones. Great for moving lots of dirt! In addition, mylagaulids also had adaptations for what is called head-lift digging, a method of burrowing that involves pressing the top of the head forward and up, compacting the soil. This requires some very strong neck muscles! Now, before you jump up and yell "Aha! Those horns were for digging!", let's dig a little deeper. With our heads.

|

| This is the skeleton of a modern mole, which is not a mylogaulid, or even a rodent. It is however a fossorial mammal, with arms and hands exceptionally well adapted for digging! |

Research by Dr. Samantha Hopkins (2005) provides evidence against Ceratogaulus being able to angle those horns properly to dig with! They just couldn't tilt their noses down far enough to really push those horns into the soil in front of them. What's more, through the evolutionary history of the genus Ceratogaulus, those horns moved back on the skull, away from the tip of the nose where they would be of better use for digging. So, the horns-as-digging-tools idea is out. What about sexually dimorphic features, like the horns that rams use to fight for mates? In those cases, we would expect to see a difference in horn size - or presence - between male and female individuals. This sex-based difference is not found in Ceratogaulus. So, that hypothesis is probably out also. But the horns are clearly providing Ceratogaulus with an evolutionary advantage, otherwise they would not be present.

Defending oneself from predators is also a good reason to have some pointy objects sticking out of your head. No one likes to get stuck with pointy objects, especially when those pointy objects are being powered by some really strong muscles... Such as those powerful head-lift-digging mylagulid neck muscles mentioned earlier. Turns out those muscles can be used for other things too, like driving a pair of nose-spikes into an attacker! The flexing of those powerful neck muscles would snap the head dorsally, the same way your neck muscles contract to let you look straight up while standing. Lots of predators like to attack small rodents. They are very snackable, and once you get a hold of one, they rarely put up much of a fight. Those same predators commonly go for the vital head and neck regions to make a killing strike. The anatomy of Ceratogaulus - including the horns and attachments for the neck muscles - would have allowed it to protect itself from attacks to the head and dorsum of the neck by thrusting those two horns at any attackers! *JAB JAB!*

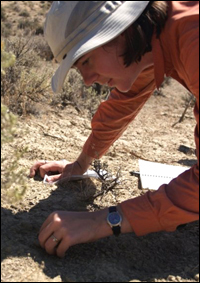

Dr. Hopkins has been kind enough to answer a few questions about her work on Ceratogaulus, including what kind of science still needs to be done to understand its biology.

How did you first become aware of the two-horned wonder that is Ceratogaulus?

I first discovered Ceratogaulus in my first year of graduate school, when I was working on the description of a new species of aplodontid rodent. I was trying to find papers on all its relatives, and I came across mylagaulids, including Matthew's original paper describing the skeleton of Ceratogaulus hatcheri from Kansas. The figure at the end of the complete skeleton just totally blew my mind. Horns? What????

What made you decide to tackle the question of what the horns were for?

The horns question was an obvious one. There's no living analog, so it's one of those questions in paleo that requires really clever experimental design. Another project I was working on had just fallen through, and I managed to sell my advisor on the idea that figuring out what the horns did would be a really interesting sidelight in a project about lineage decline in the Aplodontidae, which were quite diverse in the Early to Middle Miocene.

What was the most challenging part of figuring out what Ceratogaulus horns were used for?

The challenging part of this problem is that, given that they're a fossil organism, you're forced to work with multiple hypotheses all at the same time. The only way to come up with an answer is to eliminate them one by one until there's nothing else left. Coming up with the evidence to eliminate some of the possibilities was tough, because some of them don't make a lot of predictions for what you should observe in the fossil record. Fortunately, Ceratogaulus left us a really good skeletal record.

Is there a particular Ceratogaulus specimen that is your favorite?

I don't have a favorite. I love all the children equally. In all seriousness, the thing I find really appealing about them is the sheer diversity. There are a lot of skulls, and the horns come in many different shapes. And that leads into....

Are there any lingering questions you have about Ceratogaulus that you would like to work on in the future?

Why are the horns so variable? What does the variation in horn shape mean? We're still working on this one, and it may turn out that some aspects of the answer weren't as simple as I initially thought. We still need more specimens, and more study of the specimens we have. It's a really interesting animal, and there's a lot left to know.

|

| Cheers, you adorable little conundrum, you! |

|

| Art by Ursulav (ursulav.deviantart.com; redwombatstudio.com) |

Ceratogaulus Ale

(Ce-Rye-togaulus???) A small-ish beer with lots of character.

The Hoss was pretty good. Not great enough to make me a lager convert, but a solid, interesting beer. The flavor complexity that the rye provided really held my attention. I've had a few rye beers since, most of them being pale ales or IPAs; I have a ryewine in my fridge waiting for a special occasion also. It's neat grain, and adds some interesting flavor to a beer that I wanted to make use of when I started homebrewing.

I knew when I started putting this recipe together that I wanted the beer to be malt-driven but not sweet, with a fairly light body. The rye was going to be the star of the show, but it didn't need to be an extravaganza. Subtle and complex was to be the name of the game. In pursuit of this goal, I decided to use both regular malted rye and caramel rye in the recipe, along with a low dose of intermediate strength hops. I also used a straightforward American ale yeast helped ensure a minimal yeast-based flavor contribution. Thus was born Ceratogaulus Rye Ale. A small (low alcohol) beer with some interesting complexity, and spicy malt kick!

Type: All Grain

Batch Size: 1.0 gal

Fermentation: Ale, Two Stage

Batch Size: 1.0 gal

Fermentation: Ale, Two Stage

Date: 31 Jul 2014

Brewer: David Levering

Brewer: David Levering

| Amt | Name | Type | # | %/IBU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 lbs | Pale Malt (2 Row) US (2.0 SRM) | Grain | 1 | 57.1 % |

| 1 lbs | Rye Malt (4.7 SRM) | Grain | 2 | 28.6 % |

| 4.8 oz | Crystal Rye (75.0 SRM) | Grain | 3 | 8.6 % |

| 3.2 oz | Caramel/Crystal Malt - 10L (10.0 SRM) | Grain | 4 | 5.7 % |

| 0.10 oz | Cascade [5.50 %] - Boil 30.0 min | Hop | 5 | 7.7 IBUs |

| 0.10 oz | Willamette [5.50 %] - Boil 30.0 min | Hop | 6 | 7.7 IBUs |

| 0.10 oz | Cascade [5.50 %] - Boil 10.0 min | Hop | 7 | 3.6 IBUs |

| 0.10 oz | Willamette [5.50 %] - Boil 10.0 min | Hop | 8 | 3.6 IBUs |

| 0.10 oz | Cascade [5.50 %] - Boil 5.0 min | Hop | 9 | 2.0 IBUs |

| 0.10 oz | Willamette [5.50 %] - Boil 5.0 min | Hop | 10 | 2.0 IBUs |

| 1.0 pkg | American Ale (Wyeast Labs #1056) [124.21 ml] | Yeast | 11 | - |

| 0.10 oz | Cascade [5.50 %] - Dry Hop 3.0 Days | Hop | 12 | 0.0 IBUs |

| 0.10 oz | Willamette [5.50 %] - Dry Hop 3.0 Days | Hop | 13 | 0.0 IBUs |

Gravity, Alcohol Content and Color

Est Original Gravity: 1.065 SG

Est Final Gravity: 1.012 SG

Estimated Alcohol by Vol: 7.0 %

Bitterness: 26.7 IBUs

Est Color: 15.4 SRM

Est Final Gravity: 1.012 SG

Estimated Alcohol by Vol: 7.0 %

Bitterness: 26.7 IBUs

Est Color: 15.4 SRM

Measured Original Gravity: 1.046 SG

Measured Final Gravity: 1.010 SG

Actual Alcohol by Vol: 4.7 %

Calories: 151.6 kcal/12oz

Measured Final Gravity: 1.010 SG

Actual Alcohol by Vol: 4.7 %

Calories: 151.6 kcal/12oz

Mash Profile

Mash Name: Single Infusion, Light Body, Batch Sparge

Sparge Water: 0.97 gal

Sparge Temperature: 168.0 F

Adjust Temp for Equipment: FALSE

Sparge Water: 0.97 gal

Sparge Temperature: 168.0 F

Adjust Temp for Equipment: FALSE

Total Grain Weight: 3 lbs 8.0 oz

Grain Temperature: 72.0 F

Tun Temperature: 72.0 F

Mash PH: 5.20

Grain Temperature: 72.0 F

Tun Temperature: 72.0 F

Mash PH: 5.20

| Name | Description | Step Temperature | Step Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mash In | Add 4.38 qt of water at 159.1 F | 148.0 F | 75 min |

Sparge: Batch sparge with 2 steps (0.15gal, 0.82gal) of 168.0 F water

Mash Notes: Simple single infusion mash for use with most modern well modified grains (about 95% of the time).

Carbonation and Storage

Carbonation Type: Bottle

Pressure/Weight: 0.86 oz

Keg/Bottling Temperature: 70.0 F

Fermentation: Ale, Two Stage

Pressure/Weight: 0.86 oz

Keg/Bottling Temperature: 70.0 F

Fermentation: Ale, Two Stage

Volumes of CO2: 2.3

Carbonation Used: Bottle with 0.86 oz Corn Sugar

Age for: 40.00 days

Storage Temperature: 65.0 F

Carbonation Used: Bottle with 0.86 oz Corn Sugar

Age for: 40.00 days

Storage Temperature: 65.0 F

Tasting notes:

From Medhavi Ambardar:

"Don't change this recipe. It's great just the way it is."

From Medhavi Ambardar:

"Don't change this recipe. It's great just the way it is."

From Win McLaughlin:

" (I'm) having a hard time coming up with much to critique on your beer David. It's excellent. I like the sweet notes with a bit of hop (but not so much as to be bitter). I think I could use a touch more malt to make the initial taste a bit more full bodied and continue to balance out the sweet flavors. Dylan (my male creature) is trying it too. he says it's 'very flavorful, not much hops, not bitter, slightly fruity'."

Sources cited

Hopkins, S.S.B. 2005. The evolution of fossoriality and the adaptive role of horns in the Mylagaulidae (Mammalia: Rodentia). Proceedings of the Royoal Society B, 272: 1705-1713.

" (I'm) having a hard time coming up with much to critique on your beer David. It's excellent. I like the sweet notes with a bit of hop (but not so much as to be bitter). I think I could use a touch more malt to make the initial taste a bit more full bodied and continue to balance out the sweet flavors. Dylan (my male creature) is trying it too. he says it's 'very flavorful, not much hops, not bitter, slightly fruity'."

Sources cited

Hopkins, S.S.B. 2005. The evolution of fossoriality and the adaptive role of horns in the Mylagaulidae (Mammalia: Rodentia). Proceedings of the Royoal Society B, 272: 1705-1713.

No comments:

Post a Comment